A South African Horror Story

“Sex work is work. My work should not cost me my life. Breaking the shackles of criminalization. Decriminalize sex work now. Rights not rescue. Sex workers rights are human rights”. SWEAT (Sex Worker Education and Advocacy Task Force).

“After we are dead, the pretense that we may somehow be protected against the world’s careless malice is abandoned. The branch of the law that putatively protects our good name against libel and slander withdraws from us indifferently. The dead cannot be libeled or slandered. They are without legal recourse”. Janet Malcolm.

**

Nokuphila Kumalo was murdered on a dimly lit street in Woodstock three years ago. She was 23 years old. Beaten and kicked to death, hers is a tale that is all too familiar in the South African legal system where countless cases of violent crimes committed against women are processed everyday.

The unspoken horror of this case is not the extraordinary circumstances that led to her death. Instead it is the seemingly ordinary fate that women working in Kumalo’s profession face every time they go to work that is the most disturbing illustration our broken country. As a sex worker, (deemed a criminal act by the South African justice system), Kumalo existed in the shadows, on the fringes of society. Forced to ply her trade at night, her body like her sex, was disposable.

**

Google Nokuphila Kumalo’s name and you’ll find no photographs of her. Instead you will find repeated images of the photographer, Zwelethu Mthethwa, who stands accused of her murder. Mthethwa doesn’t like having his picture taken. Photographers rarely do. They prefer being on the other side of the lens, taking images of others.

“It’s so nice to have members of the press joining us” said Mthethwa’s attorney, William Booth sarcastically, whirling to address me after I snapped his clients image in the Western Cape High Court. Conscious that the prying eye of a cellphone camera was trained upon him, Mthethwa, bowing his head, had alerted his lawyer to my presence.

“Considering the attention that high profile, celebrity murder cases like this have attracted, your client seems to have gotten off lightly” was my instant response. Booth smirked, countering “Well, at the beginning there was considerable coverage”.

But that was three years ago. In the time between then and now, public attention has dwindled. During Mthethwa’s appearances today, the court is mostly empty, with the legal officials often outnumbering those in the public gallery. There are no troves of journalists, no grieving family members and no film crews eagerly hanging off every word of jurisprudence. Instead there is a sluggish legal behemoth limping through the hoops of juridicial procedure slowed further by Booth’s relentless filibustering.

Now however, Mthethwa has been thrust further into public view due to the inclusion of his work, Untitled (from the Hope Chest Series), in an exhibition titled ‘Our Lady’ currently on show at the South African National Gallery. Bringing together a selection of artworks from the permanent collections of the National Gallery and the New Church Museum, the exhibition aims to “reflect on the evolving canon of artistic representations of women spanning more than 170 years of image making”.

Zwelethu Mthethwa. Untitled (Hope Chest series), 2012. Chromogenic Print

Due to both the subject of the exhibition and the nature of the crime of which he stands accused, the inclusion of Mthethwa’s work has drawn vocal cries from members of the visual arts community and SWEAT (Sex Worker Education and Advocacy Task Force) who have unsuccessfully lobbied for its removal.

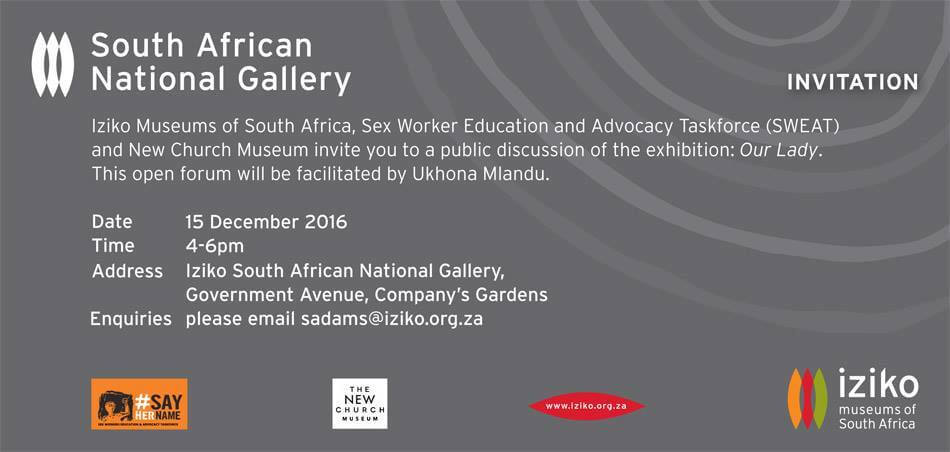

In an apparent concession, the concerned parties will host in a public discussion this afternoon at the National Gallery where the merits of the exhibition, with particular reference to the presence of Mthethwa’s photograph, will be debated.

**

Without predetermining the outcomes of the public discussion (adjective will post a follow up in due course), the key question that should set the stage of debate is whether or not Mthethwa’s work should be excluded due to the nature of the crime he is standing trial for. Phrased differently, what this asks is how, in the light of Mthethwa’s current legal circumstances, is our interpretation of his work altered in terms of the context of the exhibition and what it is trying to achieve.

Two extracts from statements on opposite ends of the spectrum are worth noting in this regard. Firstly as SWEAT activist Ishtar Lakhani, in a letter addressed to the National Gallery noted; “The irony of promoting the work of a man accused of murdering a woman as part of an exhibition aimed at empowering women, is not wasted on us”.

The “irony” identified by Lakhani is the fact that the opening of the exhibition was designed to coincide with the 16 Days of Activism Campaign designed to bring attention to the high rate of violent crimes committed against woman and children.

Then, in a joint statement issued by the National Gallery and the New Church on the 30th of November, the parties, justifying the inclusion of the photograph, maintain that “Not including this work and avoiding the difficult engagement associated with this artwork would have been easy, but it also would have been a betrayal of women everywhere”.

In light of the broader context it would seem that the opposite is true.

#sayhername