A Tally of Culture Making

In late October, around the time finance minister Pravin Gordhan delivered his mid-term budget speech in parliament and student protestors used brick paving to register their anger on the streets outside, a group of University of Cape Town students were planning something. I don’t know whether to call that something a party or an exhibition. Actually, it was both, and neither. Best to call their weekend-long jamboree a mess around, you know, like in that Ray Charles number. There was booze, there was boogie-woogie, there was attitude, and there was art.

It is because of the latter that I got invited to collage, the name of the short-lived exhibition held in a terrace home on Chamberlain Street, Woodstock. I arrived late, three days after the show ended on 30 October. Unsold beers were chilling in the fridge. US exchange student Keely Shinners was barefoot. Fellow collage co-organiser Jonathan Goschen was worrying about a French exam. And Dominic Pretorius, whose Chamberlain Street digs had temporarily been repurposed as a gallery, the entrance hall decorated with his wandering essay on walking and cityness, explained why.

Talking, unlike writing, is how people cut through the guff of ambition. Shinners, Goschen and Pretorius laughed a lot between explaining things. There was none of the whimsy contained in their invite, particularly in relation to the three large collages that dominated exhibition – “Each frame is an oubliette; pry carefully at the crevices of your desires”. I could have recorded our conversation, or written a hack review of the collages, two poems by Julia Chaskalson using recorded testimony at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, another poem by Cameron Peters, odd pillow sculpture and 13 photographs of collage’s six members in various stages of undress, including Zenobia Marder. I suggested an email dialogue instead. The review has its place in the tumbledown ecology of art journalism, but so does the interview. Their response, which collages six voices into one, follows

But, if I may, a word on the home as site of uninhibited and creative messing around. Gladys Mgudlandlu, for instance, filled her municipal home in Gugulethu with painted murals, which have become a focus of on-going artistic research for Kemang wa Lehulere. In 1978, William Kentridge, Steven Sack and other recent Wits graduates living communally in downtown Johannesburg painted a mural featuring eight figures and a flying dog over the length of their garage wall. When the mural was done, they gathered in a semi-circle and, as was the want of Sunday Marxists, held a seated discussion on “issues relating to culture and politics,” as Sack would later write.

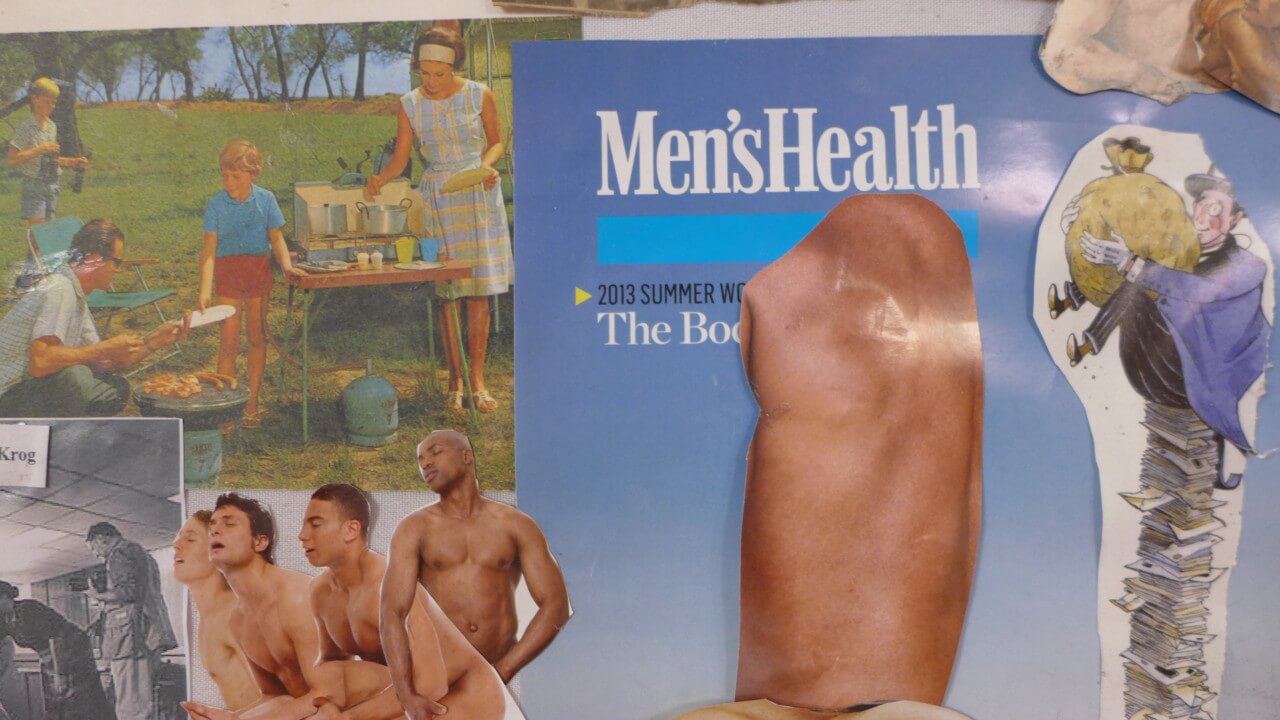

Sometime in the early 1980s, the artist collective Possession Arts staged an exhibition in art critic Ivor Powell’s Yeoville flat. John Nankin, Powell later wrote, “colonised the pantry as a space of memory, constructing a human post-box, as the focal point to a collection of personal, shrine-type memory items laid-out on the shelves”. Jane Alexander, Nankin’s life partner, exhibited a collection of bone and plaster sculptures, forerunners to The Butcher Boys (1985/86), from a rail positioned over Powell’s bath, which was filled with “a nasty reddish liquid”. Later still, in the early 1990s, arts journalists Charl Blignaut’s Hunter Street flat in Yeoville, which he shared with photographer Robert Vermeulen, was a visual ode to career ambition and cock. Pictures of newly promoted managers clipped from the business pages of the Sunday Times bordered a collage of male nudes. And so on … and to and including six humanities students with an interest in a retro artistic technology linked to sporadic moments of dissent and critique globally.

Adjective: None of the core members of the group are art students. How would you describe your relationship to art and the Cape Town art scene?

collage: The Stevenson, the Goodman Gallery, the South African National Gallery, Gallery MOMO, 99 on Loop, sure we go, have a look around in the empty gallery, leave, build up pamphlets on our bedside tables, a tally of culture. We go to events at Knext, and The Nest (before it closed), and try to be hopeful about young people making inroads into the market. Let’s not flatter the market with the label “scene”. Maybe that is a bit negative: the recent exhibition The Quiet Violence of Dreams gave a real sense of there being a community in conversation with itself, a gallery culture that was aiming for meaning, rather than money. To walk from the real streets of K Sello Duiker’s fiction, into a multifarious imagination of place and person and art was a meaningful instantiation of what being able to relate to “a scene” would look like.

To get to the point, we are humanity students not willing to accept that the art market is a monster that one needs to be eaten by to get into: study at Michaelis, make some connections, make a break at a private gallery, and then settle into being a digestible professional artist. Some of us have worked at galleries, done interviews with prominent artists. But, needless to say, we call bullshit on the sterile proto-capitalist-culture First Thursday phenomenon. We want to slash the stomach of the art scene from the outside, you know, put some dirt on the walls.

Adjective: At what point during your creative process did you decide to hold an informal exhibition/party at your shared house in Woodstock? And why the decision to hold an exhibition?

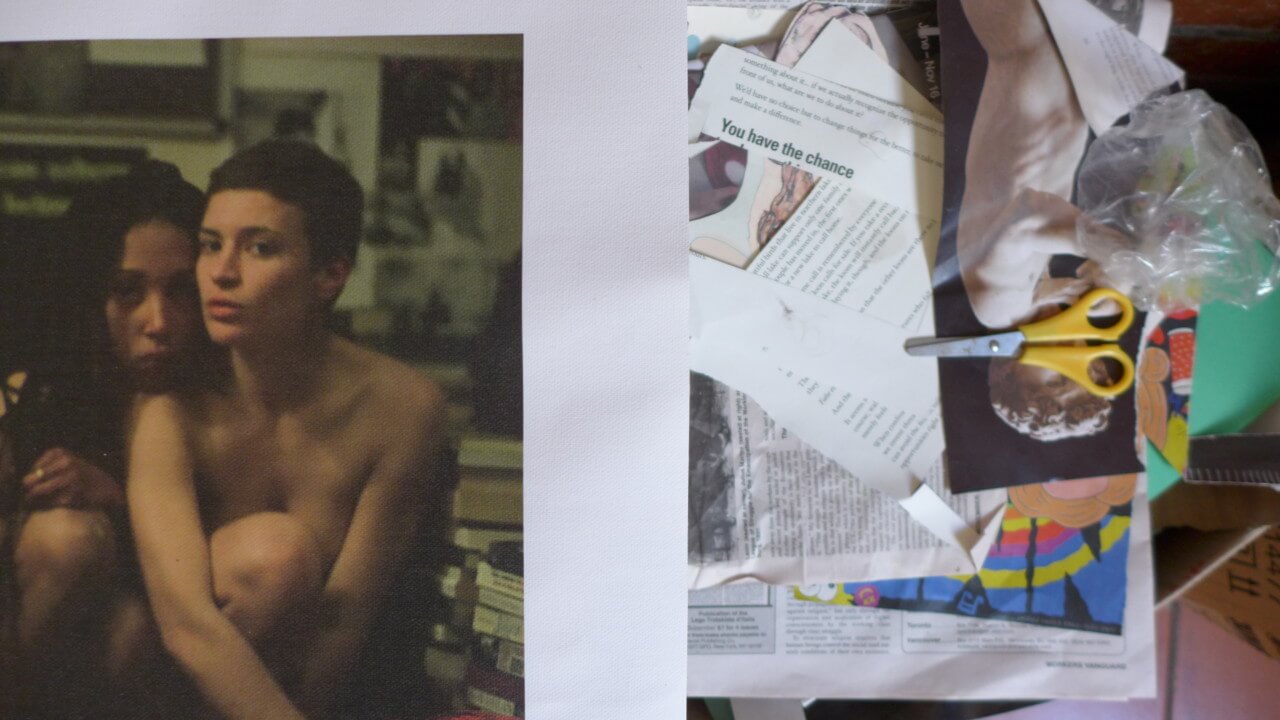

collage: There was never a plan to exhibit. The collage started in July with two people coming home after writing an exam at university, and then spending the evening drinking wine and cutting up a few books and magazines and sticking their creations onto the blank wall. Over the following months, dinner parties, and random afternoons, often descended into a haze of bodies, glue, paint, and scissors. We did host one Collage Party, the day before the municipal elections, actually. The invite read:

- motherfuckers. we wanna do some arts and crafts with all of you. please come and get fucked up and make pretty things and shit on our big empty wall. please bring books, paint, crayons, magazines, and interesting material, scissors. we will provide cuntloads of prit and prestik. we have only 2 objectives. get too fucked up to vote on Wednesday, and put shit art on the wall. please see terms and conditions, bitches. terms and conditions: if we one day make a lot of money from selling this collage, fuck all of you, we will claim this “material portrayal of the zeitgeist of the age, the collective consciousness of an age when the youth had no point of authoritative reference and just a sea of conflicting, fragmentary references.

We did vote. After a while, as seen in the above invite, we started to feel that there might be something in it. We started to believe that our trashy recreational activities with friends might mean something. Newcomers would stand in front of the wall for a long time, contemplating, laughing, before adding their own shit. That is, people, other than our selves, were actually interested. Maybe that’s what art is. We had to take it down at some point before the end of the year when many of us leave Cape Town. So, we decided instead of throwing it in the rubbish we would preserve it. We built canvases, spent hours transposing and curating the collage from the wall onto the canvases. And then we started playing with the idea of an exhibition.

Adjective: Why exhibit in your house in Woodstock, as opposed to a hall or warehouse?

collage: At first, we thought of hiring a gallery space in Woodstock. It was going to be too expensive, and we were probably getting ahead of ourselves in terms of how many people would actually attend. So, we decided on hosting it at the house. Beyond the practicalities, the choice seems obvious now. We want to make the personal public. And, having it at home allowed for the “exhibition” to emulate the very process that produced it, because part of the exhibition was a participatory section where people could collage onto a blank canvas that was already prepared. The exhibition turned into a three-day long affair of people coming and going, drinking, making. At one point, 15n or so people were sitting on the floor so engrossed in their creativity that one couldn’t stand and view the already made art. That’s exactly what we wanted: people to stay in the “gallery” space and feel comfortable doing so. The “gallery” was no longer a place to go and consume, but rather, an intensely personal space to consummate with. One visitor to the exhibition bit his hand until it bled and fingerprinted the collage.

Adjective: How do you see the various components of the exhibition functioning in relation to one another? Is there a connecting thread?

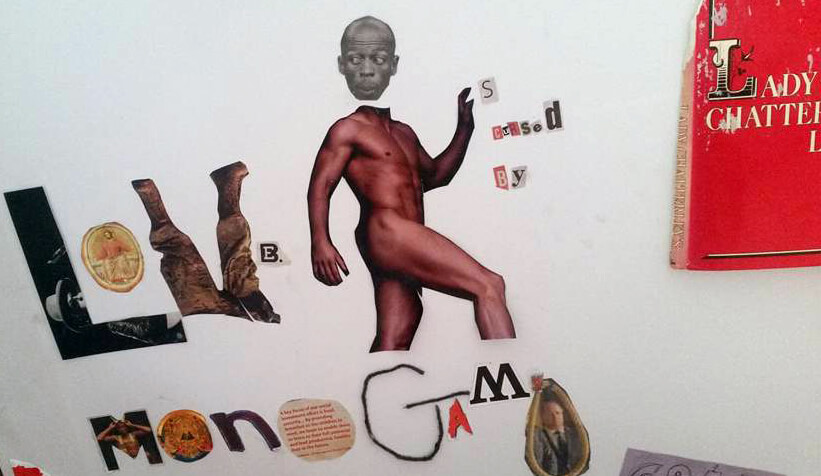

collage: The exhibition was a collage in both content and form. Apart from the centrepieces – two completed multimedia collages, and the in-the-making collage – there was a photograph series, an installation piece, poems and a short story as writing on the wall, and other apocrypha. Some of the poems were found poems from the TRC, the literary equivalent of collage. The short story was, most simply, about a mind struggling to hold, without reduction, the images and experiences had while walking the streets of Cape Town. The installation piece was the enshrining of the everyday-objects of a romantic relationship (books, underwear, menstrual cups, butt plug, love notes, etc.). The connecting thread is the desperate attempt to capture our experiences and the essence of collage is the belief that this cannot be done in a single medium, or within a specific master narrative.

To borrow a concept from psychoanalysis, the creation of a meaningful personal narrative lies in the transference between subjects, the liminal space of conversation. So, sure, the various components of the exhibition are talking to each other, simultaneously positing themselves and negotiating the connective tissue of the exhibition as a whole. The connecting thread can be seen as the striving towards capturing the sense of a point in the fabric of time and space. There is no definite thread, but rather, a double-backing pentimento in the form of a gyre of narratives that is both centrifugal and centripetal, that is, moving towards and away from a point.

Also, the viewer is in conversation with the various pieces, which inevitably leads to them imposing their own dialogue onto the silent stage. Collage escapes delineation; and thus meaning, if any at all, exists only along the seams, beneath the overlapping, swirling in the free association of a viewer’s mind. We could say many things to satisfy your desire for meaning. Each frame is an oubliette; pry carefully at the crevices of your desires. This is not a solo show. This is not a group show. This is not a collective’s show. This is the death of the artist. This was hardly art before it was hung on these walls. This is a material representation of the zeitgeist. There is no authority. There is only a mass of fragments, conflicting significations. An imaginary ripple in time and space. Culture that happens to be youth culture. Youth culture that happens to be protest. Laughter that turns in tears. This is you. This is us.

Adjective: The collaborative collage works dominated your exhibition. Why collage? Why collaboration?

collage: Before we had the exhibition and labelled the works “art”, the works already had value. The real value rests in the hours of love, friendship, tears, and fun that went into the project. Most art is individualistic and only gains public value (beyond the artist’s own value) through the commercial gallery. The professional artist labours away in an inaccessible private space and then pleads for public recognition. This process reduces “public value” to “monetary value”. Whether our exhibition is famous or sells is irrelevant. Our project is a radical renunciation of the individualist and commercial art world. Moreover, our process was never guided by aesthetic theory. We acted first, authentically, and then aesthetic theory can be used to explain it and retrospectively add value to the process, rather than the other way round.

The pieces engage with history, both social and artistic, both local and global, and the present, and the personal and the political and the pure and the obscene. Henri Bergson talks of durée, a conception of identity through time that says that all personal and collective history snowballs into an ever-present time that contains all-time. Collaborative collage seems to be an apt way to represent experience seen through this temporal lens. Moreover, the collaborative collage method is a politically radical gesture. It democratizes both the creation and reception of art. It requires little technical skill. Most people are visually literate. It allows you to put tampons on the wall. It is a both a destructive and constructive process of destroying the canon/hierarchy/monopoly and then remaking, reframing it in our own terms. You should watch the Věra Chytilová’s spell bounding feminist film, Daisies (1966), to see the full potential of the collage aesthetic to be politically and socially radical.

Though, of course, we began constructing what became the exhibition’s grand finished canvasses out of a kind of creative pragmatism necessary to non-Michaelis humanities students. We used the materials we simply had at hand – words and junk. It’s interesting to reflect now, with the completed development of the eventual collage concept safely behind us, that the surrealist/Dadaist impulse that runs through the overlapping anarchic energies of our display pieces has its own historical antecedents in many other moments of prodigious social upheaval throughout the twentieth century. The Cubists pioneered the technique just before the First World War, the Cabaret Voltaire applied its principles violently to all mediums in Zurich in 1916, the Berlin Dadaists of the Weimar period (Hannah Hoch, Max Ernst, George Grosz) used it to ridicule their post- and pre-apocalyptic world with impunity, the Sixties student generation in America and France took the teachings of Guy Debord’s Situationists to heart and saw society itself as an arbitrary construction waiting to be “detourned”, the punk and post-punk era in England saw all frivolous materials of pop culture (magazines, songs, films, TV interviews) swallowed up into the gaping maw of negativist rearrangement and then the Style Wars of the New York underclass in the early 1980s birthed the remix mania of Basquiat and hip-hop that we are still in the lengthy process of inheriting.

All of which is to say that moments of diverse class struggle seem to ensure the temper-tantrum aesthetic reaction of “rip it up and start again” that Fallism itself seems to have reintroduced into our lexicon of daily projects. Collage in this sense just takes its contemporary position in the now timeworn tradition of Creative Destruction.

Adjective: The exhibition and its work was greatly enabled by the shutdown at UCT. It gave you time. What is your relationship to the Fallist Movement?

collage: Most of the work was finished before the shutdown. However, it was probably the shutdown that led us to actually organizing an exhibition. The reason for this probably lies between 1) we were bored and privileged and had free time to bring an idea into reality, and 2) feeling buoyed and impassioned by the movement to believe in the value of youth culture. However, maybe neither of those points is true. It is also possible that the whole project, even before we decided to have an exhibition was done out of a complete cynicism about social and political spheres. Maybe it was a retreat into the inner impure citadel, a place where we could create a space completely free of all the reduction of the political, both conservative and progressive. If you go so far left, it becomes right.

The truth probably floats in the dark, somewhere between all those ideas. Must be unpalatable to those who do not like honesty. Movement is a strong term. We see ourselves within, but to some extent on the peripheries of the current student culture. We go to some protests, when appropriate. We want freedom and equality and radical change. But, don’t look to us for any definitive words. History, this converging of lives, cannot be given an opinion, encapsulated in a judgement. Fragments of mirrors are stuck to canvases; what are you looking for?

Adjective: How do you see the exhibition extending the aims of the Fallist Movement, if at all?

collage: Many of the images and ideas scattered across the collage definitely fall into the orbit of the Fallist Movement. Identity politics, radical economics, anti-establishment views, etc. The art is an expression of a disillusioned youth, trying to come to terms with being pawns to social situations that were scripted many years ago. Pawns are both the most valuable and least valuable pieces in chess. The movement could be criticised for its contradictory claims of definitive moral high ground, while at the same time, a decree of absolute absolution of hierarchies. If you think this way, then you could see the exhibition as offering a slightly more ambiguous view of things, leaving issues open ended, and solutions elusive. Nothing is sacred in the collage. But, this way of thinking is probably in vain. Over 40 people worked on the collage; the “movement” is made up of thousands. Some definitely want to extend the aims of the Fallist Movement. Some, probably not.

Then again, at the end of the day, we cannot determine how you read the work. Do you read me?