Simphiwe Ndzube

In this issue of Perspectives, adjective talks to the recent winner of the Tollman Award, Simphiwe Ndzube whose show Becoming is currently on show at WHATIFTHEWORLD, in Cape Town.

The Tollman award, big news. Did it come as a surprise?

Simphiwe Ndzube: Ja, no, definitely. It was unexpected. And also not being associated as an artist at the Stevenson, cause it seems like its all their artists that have been recognised by the award people, so ja. I knew when I was nominated and I thought ja cool this is amazing. So then I had to send some works and two weeks later I heard the good news.

This is not the first time that you’ve been subject to a major award winning the Michaelis Prize in 2015. Was that equally as unexpected?

SN: I dont think the Michaelis prize was so much of a shock because of the feeling that most people had and I had. But for me as I worked through the year I didn’t think of the Michaelis Prize…it wasn’t even in my mind. So when I got it, it seemed as if if was a pat on the back and well done and now off you go. It is a big thing, but I don’t seem to grasp the idea of awards so well but lets see as my career goes.

Now I’m interested in the work that landed up in the National Gallery…Raft. Because that work, past your life with it, like a raft has taken you on a journey in a way… but it’s been quite important for you as you’ve begun to make your stylistic stamp on the artworld, can we talk about it in terms of some of the themes that you are exploring in your current show. As a way of an introduction can you tell us a little bit more about who these figures are that inhabit your world.

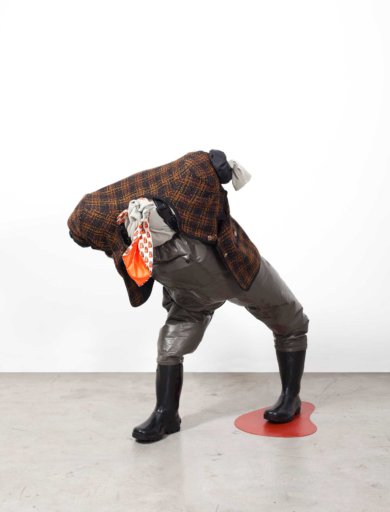

SN: Most of these figures have changed…I’ve had different kinds of figures appear in my work, I’ve had figures that are dandies which are completely concealed, I’ve had figures that are completely grotesque, amputated, not fully formed…so now where I’m at at the moment…I’m making these figures that are partly split in two.

So there’s the worker underneath, wearing the boots…it could be the mine worker, the fisherman, and then there’s these bellies, these big upper bodied figures that look they could be politicians or the wealthy master, but at the same time they’re like waste bags on top and money bags on top. That’s an idea I started with in third year when I was looking at excess and exclusion so I combined both the body that is fat, that has got these body lumps, these really really really fat bellies with money bags and waste bags and then contrasted them with figures that I never actually got to make…but I was supposed to make these skinny, really broken figures and have them contrasted together but I never got to make that.

So these are the figures that remained in the work…so who these bodies are…? To me they are both what Fanon talks of as the Wretched of the Earth, so they really are not blessed but I play around with the master and the slave body, which I mix together. Because at the same time there is almost a pop sensibility which is almost celebratory, and not abject…

SN: It’s very celebratory…they really playful which has got to do with my approach and how I make the work. Some of the work has turned out to be quite violent when I look at it but when I created it I was really having lots of fun…pumping music and that…

So to go back to the Raft that you mentioned, I was looking at a particular space when I was creating the Raft…it was the first work that I started off in my fourth year and it was the last work that I finished off with…so I really got to meditate through it…to make it a really finished and complete piece.

It came about when I was looking at South African townships in general and how they are in themselves like a raft…sinking within there own clustered, contained spaces… especially where I come from, in Masiphumelele, my hood really looks like it’s a raft in the sense that it’s a really small township in a valley, so that was my departure.

So that’s where I started off by looking at a space in relation to an object or an event. That’s also the same time that the migrant crisis was happening…it had been happening for quite some time but it had really came on strong on TV around April, so that somehow had an influence on how I looked at the space, at the sinking and the violence that happens in different kinds of spaces.

Democratic South Africa, the country that we live in now, is only 22 years old…post democracy. For much of that period the youth has been written off as lumpen, as having no distinct political agenda. As evidenced by the student movement in the past two years, that is changing. How important do you think it is for work to be concious of it’s social economic political surroundings and the power to talk back?

SN: Personally, I think it depends on who prefers to do what and to decide on what kind of trajectory they want their work to take. So for me personally, I felt the obligation, being black in this country at this time there is somehow a obligation to speak back to the times, the reality of what is happening. It’s something that we all cant avoid, we live in this time and we have these conversations, our ways of seeing and doing are affected by the ways in which we live…but it’s something that I’m starting to learn this year…I’m not really putting meaning into the work, so the objects that I collect somehow decide what the meaning is.

It’s interesting to me..the way in which those objects have transcended beyond the current conversations that we are having to conversations that could be references to events events happening outside South Africa. I think I’m actually quite interested in broadening that conversation but at the same time having work that has a relationship with where we’re at. The work that I’m creating now…I don’t think that it speaks so much to the current situation in the country, but there are objects that one could isolate and say ok, maybe this is about that, but in this current work I’m making one could look at current conversations around human movement and migration and all the way into the dump, waste culture and who recycles and receives the end of that…to conversations to disability which are quite global…

How does that figure? Do you have experience of people with disabilities or is there something else that informs that?

SN: I think it’s something that somehow has managed to capture my psyche in the way that I hope to understand the body because I don’t see peoples bodies as perfect. We put on these clothes but we are concealing so much that is different I have and what other people have, so for me it is to play around the possibilities of what the body could be. That is quite important for me. I would not say that I have any close relationship with anyone disabled at home but I relate it back to my experience of the art school where I felt that the education that I’ve had was so crippled which ended up being something that I could play with.

In essence is their a sense of justice in your work or is it a passage to addressing some kind of justice in your way of seeing?

SN: It’s more of trying to understand the world. I don’t know if my work can perform any kind of social justice at all. One could look and find different things that somehow one would say are conscious of what is happening around me…

Your figures are always veiled. I’m quite interested in the presence of pattern and textile. Your play with the materiality of the surface and the juxtapositions of different materials. How did you arrive at the aesthetic?

SN: With the patterns, I wouldn’t necessarily say that I started off with Shweshwe but I think that patterns perform a different kind of visual stimulation to the eye. Sometimes, not necessarily to understand what that pattern is saying but how it is repeated and what colours are used.

Ok, also, I need to be clear that all the clothes I use in the work are all second hand, found clothes. So I look at the possibilities of different kinds of materials and what they could do. I don’t necessarily try to understand and know the history of the patterns and where they come from, but I operate mainly on the possibilities of how I can push that pattern to look in relation to a different kind of form or a background where the colours are really exciting. So I respond mainly to that. There are some patterns that I have somehow deliberately used…like the military camouflage and to play with the idea of disguising the body in a landscape which has nothing to do with that particular pattern.

Mainly the most important thing to do with the articles of clothing that I collect is to conceal the body, to adorn it with these materials so that gender and race are somehow partly concealed and then you look at the body without being limited to those particular readings.

Far from being individually isolated objects they begin to form props in a narrative. I don’t want to impose or even to limit asking you what that is, because it closes down the possibilities of meaning and interpretation, but talk me through the way which in which you bring that process about…I’m interested in the way you set dress…

SN: I’d say that if maybe we look at the ties, my first reaction to a tie was “my god, this is such a stupid thing who would invent this thing that could potentially be used against you”…but then I started looking at the possibilities of what this tie could do beyond what it is meant for…immediately when you look at it, it looks like a cobra, a charging cobra…at least that’s what I see when I look at a tie, so then to give the tie those characteristics but then to carefully choose between the colours and the patterns…so to push the tie to activate the object in order to push the imagination. I’ve come to learn that my imagination has endless possibilities when I practice using it.

It comes with looking at something that is simple and harnessing the possibilities. Another object similar to the tie is the brick or the cinder block…I associate them with the RDP (redevelopment project) housing and the hope that a lot of South Africans have been given throughout the years, 22 years of being bombarded with promises, so that brick for me functions as a symbol of promise and to subvert it…to take it, make it out of wood and burn it and then suspend it…that starts a conversation of construction and destruction which I think is a conversation that seems to be reappearing in my work…these double meanings of things.

The umbrella has also been a reoccurring motif, as in the Raft which is in the Iziko SANG where it was used as a metaphor for a sail…I’ve noticed that it keeps on cropping up in your assemblages…

SN: I think the umbrella, much like the tie is both a weapon, but is an object that is used to protect the body. So it extends the conversation of the body protected not only now by the articles of clothing but also by an article that is also meant to protect it from elements. But first and foremost I just really really like the form, it’s beautiful, in relation to the body this organic form of the umbrella I try to integrate with the body to speak a similar language to my figures.

The morphed physicality of your figures is quite disarming…

SN: Making work that needs to travel and come back presented a problem so I got advice from my sculpture professor Jane Alexander and she suggested that PVC pipes as an armature is quite a durable material…better than metal which I had used but then it rusts over time and it’s a heavy material to work with…the forms go back to the possibilities of what the body could do and what it can look like.

But with the sculptures what I’m interested in, especially being in Woodstock, I’ve been observing the people around the streets, the community. There are people that are always carrying things, collecting things, materials which fascinate me and sometimes I buy my materials from them…so somehow some of the movements, the distortions of the body and how much it can carry I see on the streets when I walk out of Greatmore, in people that are recycling things. Some of them really not in good health, walking with crutches and still pulling these things along trying to survive. Not to say that the work is particularly inspired by that but it forms an extension into some of how I make the bodies. But it’s important that they become really stuffed with things. Firstly I was using clothing but then they were so heavy, so then I’m using this stuffing, which is lighter but still achieves the same visual impact.

When you’re beginning with the compositions of these figures do you look at any historical references or do they emerge as you go?

SN: It’s more of a sketch actually especially with the perspex photographic paintings as I call them. All of the figures are me and I’m wearing all of these items and I’m covering myself completely, you cant even see it’s me, or if it’s a sculpture or if it’s somebody that’s breathing underneath it.

So, I don’t work from any references but because I collect a lot of materials and of course the materials strike a visual possibility, so I think about how I could manipulate them…So the compositions emerge purely as sketch. I started off doing those perspex paintings because I was thinking about compositions for my sculptures and I used my body to see what the next feel of the sculpture would be but actually map it in a photograph…but as I put them all together in the studio they made a really interesting conversation that is asking to be a work by itself.

I started printing on perspex in 3rd year of myself concealed in fabric but then it looked somehow very similar to Mohau’s work which is so beautiful, so the question was how to make it my own. So with that frustration I experimented and this is where it ended up.

How much ‘of you’ are these sculptures? Are they your own monsters or parts of your psyche manifest in the world?

SN: I’ve never looked at it like that. But the same thing happened to me at the National Gallery after they had collected the Raft. I went to look at the work and I could not believe that I had made that? I asked myself what was I thinking…and I looked at it after not having seen it for a while and I had the same questions…what was going on in the artists mind. I saw it differently looking at it from the perspective of not a creator but of the viewer.

But with that way of creating I guess my work probably has to do with my psyche and not necessarily me projecting myself into the work, but again because we watch the news, we see the world…I’m very aware of people so I look at people…so it’s how I see the differently abled, different kind of people, and then translate back into sculptures.

But in many of them I honestly don’t understand what is going on, I’m drawn to a juxtaposition of the possibility of these figures and the tension that the bodies can have based on what material has been used and how I’ve pulled and stitched it to represent something.

Eventually what I’m trying to portray is a different sensibility to the body, because these bodies are really fragile…diseases, being born in a particular way and so going back to a question of what do we deem as normal…so which bodies are normal. If I make bodies like this because I see them all the time, then the sculptures can make you look at somebody that you would completely dismiss on the street as full of possibility.

Also because the people that look at these works are really privileged people and what I was saying about noticing different people in Woodstock and taking elements of that and putting it in a gallery where people consume it…it’s not my mission to draw peoples attention to things that they would otherwise notice but in the bodies that I create do shift that idea of what is normal and what is not so I make my weird bodies normal to me.