Fatally prejudiced

No local artist is more provoking, more irksome, amusing, or outrageously on point than Ed Young. If you adhere to J.M. Coetzee’s diagnosis of all things South African he’d be fascinating, loathsome, and of course disgraceful. This view however is stunted, reductive, and fatally prejudiced. It was Lawrence Alloway who coined the phrase to indict Clement Greenberg, the guru of Ab Ex, of an aesthetic myopia. Alloway was right – Pop Art rules, shaping every aspect of contemporary life, the way we look at food, entertainment, sex, understand time, and absorb ideas. That said, a fatally prejudicial mind-set, under the banner of political correctness, is also thoroughly entrenched. The moral high-ground is king, these days there is no wriggle room for provisos, caveats, let alone doubt. Ours is the hell of absolutism.

It is within this intolerant climate that Young operates best by tilling our ills, inversely parading our ‘likes’, in effect setting us up as the prurient moralists and bankrupt ideologues that we are. His Teddy Bears, furry lookalikes plumped on a plinth with middle finger thrust upward, at the ready to irrigate our squirming arseholes, or with his paw dolefully at play beneath white jockey underpants, as a reminder of our masturbatory self-love, T/ed’s dick a selfie-stick. Or his hirsute hyperreal mini-me hanging from a nail, naked barring a pair of Xmas stockings for socks, a spoof of a comic male oversight in so many sex scenes. Or then again Young’s latest piece of porno, shown at the Joburg Art Fair, alongside a word-work THANKS FOR COMING, of a couple of dwarves beating the crap out of each other in the Company Gardens before skipping hand-in-hand along its leafy lane.

Who is his teddy bear cocking a finger to? Why are his dwarves, dressed in blue and red short-sleeved t-shirts and white jockey underpants – a favoured dress code – hating and loving each other so? As for the artist dangling from a nail? The piece is called My Gallerist Made Me Do It. Really? Bullying aside, Young owes too much here to Maurizio Cattelan. Then again the work is not just derivative, his works are not just facile copies, they come with scare quotes. His is a mind and imagination wired to something far more than the self-reflexive love-in we call the art world. Those oversized red socks, suggestive more of a Xmas stocking, contain only the extremities of a gift – Young, the artist as a bare-forked animal, it is the mortality of the artist, and not merely his acute intelligence, which makes his works as insulting, as outrageous, as they are deeply stirring and all too human.

As a witness to Young’s fight club at the Joburg Art Fair remarked, the dwarves – bodies which remain difficult to appropriately name – are unholy ciphers for the Economic Freedom Front and the Democratic Alliance. This may be the case or not. What matters is that we are thrust into a strange and estranging mix of violence and fraternity as meaningless as it appears to be earned. Watching the movie and recognising the cultural hub surrounding it – the Iziko National Gallery and Natural History Museum – underscores the fact that what we are seeing, or more often than not refusing to see, is an appalling spectacle that refuses to be framed as a performance. Like everything Young has made, this is and is not art.

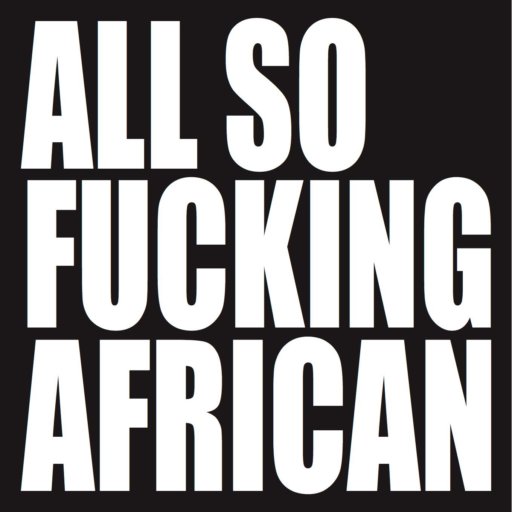

A familiar blur in an art world which has long lost its compass, this refusal or inability to name and fix a thing, permit its self-presence, in favour of some vague portmanteau – ‘contemporary art’ – reminds us not only of the obscenity of the art world’s current moment, but the hapless role which all things ‘African’ now assumes within its orbit. ‘Everyone is all of a sudden so African’, writes Marisha Flovers. ‘The restructuring of global and national art spaces with a focus on newly found Pan-African intent echoes the state of contemporary Art in 2016. Like a rebellious teen screaming out for recognition and acknowledgement, Africa has clambered into a pigeonhole of “black essence”, clinging on to the sterile, desiccated concept of intrinsic blackness’. This is how Flovers kickstarts her interview with Young. Her focus is the 2016 Armory show in New York in which Young showcased the word-work ALL SO FUCKING AFRICAN. ‘It’s a commentary on what is happening around me’, Young remarks. ‘It comments on using blackness for the sake of blackness. I mean, it’s good for transformation, but it a bit late. All of a sudden, everyone is just so African’.

The context, the Armory show, deserves further reflection. We’re in New York and Young is exhibiting under the outpost of ‘African Perspectives’. As Flovers puts it, ‘Curators Julia Grosse and Yvette Mutumba wanted to provide a glimpse of contemporary art whilst moving beyond the conventional ideas of the African continent’, hmmm … ‘We’re offering this platform, to help people realise that African art is just as non-existent as European Art’, hmmm again. Then co-curator, Julia Grosse, contributes a further bromide – ‘basically an artist is not “African”, but rather, contemporary, just like every other international artist’.

Just like? Are we in a game of charades? Any attempt to define the ‘singularity’ of anything ‘African’ is Flovers core concern, because it is Africa as widget which assumes centre stage. And here Young operates brilliantly. ‘I am an artist’, says Young. ‘I may not be seen as an African artist in some spheres, but it doesn’t matter. Africanity doesn’t exist’. Well, stick that in your pipe and smoke it. The riposte, in keeping with Mutumba and Grosses’s desire to de-found and demystify the addled conceit of Africanity seems nigh – but not quite. Under the vainglorious banner of political correctness the fetishisation of all things African has become big business. Witness the book in Contemporary African Art Fairs worldwide. The industry, taste, exchange economy, politics has flipped overnight, ever-ready to atone for its sins or in the case of that awesome cross-dresser, Superman, the sins of others. Young sums the toxic brew of pragmatics and good will – BLACK IN FIVE MINUTES.

Other word-works – I SEE BLACK PEOPLE or ALL SO FUCKING AFRICAN or BLACK PUSSY (which was never made, though you’d never guess given the apoplectic outrage it provoked) – works writ large in white on black. Purged of the cloying knowingness one finds in Barbara Kruger’s dated word-works, or the highly durable high-wire acts Jenny Holzer, Young’s word-works are devastatingly on time. I SEE BLACK PEOPLE, a work exhibited by the Smac Gallery at the 2015 Johannesburg Art Fair, reads as a straight-forward observation. One might assume the first person pronoun – I – to be a subjective perspective of a white male artist. This would be true, but it is also not. The statement does not read, I, Ed Young, a white South African artist born in Welkom in the Free State, see ‘black people’. The statement could as easily be read as ‘I’ a black person see other black people. But because we know the artist to be white, male, and a shit-stirrer, we fixate upon what could be interpreted as a racist abstraction of others. The generic conflation – ‘black people’ – is now not read as an objective sighting of a cluster but a derogatory diminishing of a corpus of singularities into a blurred group. And yet, given the context for the exhibition of this statement – a forum and culture which in its very nature is exclusionary, elitist, and predominantly frequented by a white elite – surely this sighting is inaccurate? Surely what Young is also telling us is that he does not see black people? That black people are markedly absent from a forum – one of Africa’s leading art trading centres – and, therefore, that it is their absence which is all the more palpable?

Returning to the 2016 Armory Show, Young proffered two text works – ALL SO FUCKING AFRICAN and BLACK PUSSY. The second work, deemed unseemly and unsightly, was not exhibited, and in the light of the recent Trump expose in which it was revealed that that fascistic moron had publically placed his teddy-like paw on a woman’s private parts, one can understand the outrage which Young’s BLACK PUSSY may have generated. But Young is not Trump. If Trump is guilty of misogyny and sexual assault, Young is culpable of a psychic assault – one which I deem urgently necessary. Let’s read ALL SO FUCKING AFRICAN and BLACK PUSSY in tandem. What are we to make of the first work? Is Young being dismissive of the populist and pragmatic interest in contemporary African art? And if so, does he have a point? And why, in the light of this point – the new-fangled fetishisation of African art – should the second work, BLACK PUSSY, be struck from the show? Surely the fetish of Africa, rooted in a rapacious and libidinal investment in its iconography, its body, its economy, is deserving of critique? That the continent has long been perceived as the cradle of humankind, with the woman’s fertile body at its epicentre, means that there is nothing inherently obscene in Young’s work. If so, then what are we to make of Gustave Courbet’s far more visceral painting a woman with splayed thighs and dubbed the ‘Origin of the World? There is of course yet another twist – a ‘pussy’ is also a coward. Is it therefore not ironic that the curators should choose not to showcase the work? To censor it, and in so doing amplify its erogenous allure?

All the brouhaha and fuss conceals an obsessive-compulsive obsession with and denial of Africa as fetish object. It is this conflicted obsession which Young exposes. It is not that Young is indicting the newfound provenance of contemporary African art, or that he is directly judging those who invest in its economy for being prejudicial or slanted in their understanding of African art, or even that he is rendering absurd the very notion of Africa as a unified whole or force-field. It is rather the artist’s ability to set up these contentious reflections that matters. That he has elected to write ALL SO FUCKING AFRICAN rather than ALL SO AFRICAN underscores the fact that African art, art from Africa, is shaped by a rapacious economy, and here Giles Peppiat’s unfortunate phrasing of the current interest in African art as a ‘second scramble for Africa’ reinforces Young’s concern. By associating the current appropriative relation to all things African with a colonial inception – the carving up of Africa after the Berlin Conference in 1886 – Peppiat has drawn a stark and ugly connection between past and present, Africa then and Africa now. Young’s goad is designed to ask us to reflect upon and inflect our vision of Africa differently. He is not asking that we be more progressive, more ethical, that we rethink our relation to the body of Africa – its personhood, its being, its rights – but in lieu of the inferential and inductive nature of words this is also a way of looking at and reading the seemingly blunt white text scored across a night-world of black pain.

There is no doubt that the construct – Contemporary African Art – is an afflicted and contentious one which cannot and must not be absorbed by the dubious polity that is Political Correctness. As I have stated on numerous occasions the newfound obsession with Africa is not merely a rapacious echo of the past but, all the more importantly, the optic in-and-through which the world must rethink its humanity. Africa would bequeath the world a human face, Biko remarked. This face, if it is to be human, must embrace its night world. It is worth also noting that Biko did not speak of a black face or a white face, male or female, rich or poor, heteronormative or transgendered. Africa is not a placebo, sex toy, plaything, or confessional booth, but the core of an inclusively regenerative ethical drive. It is in this context that Young’s word-works will help us to reconfigure our prejudices, our fears, and our fantasies. If the global Contemporary African art world is stricken and morally questionable this is so only in so far as it chooses to parade its falsities. Whether we are regressing or moving forward is disputable. I would prefer to hold onto this suspended and divisive moment, and, therein, reflect upon the works of those who have contributed to both the difficulty and miraculous qualities which, for Ben Okri, have allowed for the most daring and most sublime acts of creativity.

What Okri and many others are warning us against is a fatal prejudice. This indictment of the reductive optic through which we choose to look at and appraise the world is all the more critical today, for it is our knee-jerk dismissiveness, our race-fixated divisiveness, which denies Biko’s vision of a more inclusive and more heterogeneous ‘joint culture’. For all his seeming outrage Young is not the culprit here. It is those who in choosing to interpret his word-works from an unthinking, uncritical, and dangerously prejudicial and jingoistic position who have contributed to the diminishment of our embattled art world.

On the toilet door of my local internet café in Observatory, Cape Town (which by the time you read this will have closed down) I came across the following anonymous graffitti. It begins with an obscenity then segues into a richly enabling world view. The first statement, penned in blue, could have been a word-work by Young. It reads: WANNA SUCK BLACK COCK. There is no concluding question mark. As Coetzee reminds us in an early novella, The Vietnam Project, we write on walls to abase ourselves before them. WANNA SUCK BLACK COCK is such an abasement. At its core lies the pathological fetishization of the black male body. But it is the words penned in blue by another hand which sharply shifts the axis. And it is this anonymous mind and heart which sums up my own ethical position:

do I want to suck black cock?

do I suck black cock?

I think both are absolutely irrelevant

if all I am here 4 is a SHIT

lets be civilised here – and

just realise that there are far

more suitable situations

in order to ‘SUCK COCK’

than this skanky toilet.

Lets concentrate

on

being free and

real – less judgemental

and open

enough

to freely act

on a taboo

fantasy

and in fact

celebrate

the exploits

of people with

pure and kind

motives

no matter

what activity

they choose

to engage