Igshaan Adams

The second installment in Perspectives features artist Igshaan Adams who talks to us about his show Oorskot, currently on view at Blank Projects in Cape Town.

As you said the other day when I visited your studio, you said that you have got bored of making flat squares on the wall, and you were looking for a solution to take your work into a more three dimensional scope, maybe as an introduction can you give us a talking point through that…

Well, for about a year and a half I’ve been weaving these tapestries, and they all ended up in a square and rectangular shapes, so in that process all these mistakes happen, these different mistakes that you think can be developed and forms that I really want to develop further, so after the last body of work of tapestries, the intention was to see what happens when they didn’t have a space, I tried to find someone who I’d like to collaborate with, there was potentially someone in London whose forms I’d seen, and I thought it would be beautiful to turn those forms of hers into looms and then weave into them, kind of creating skins, but logistically it was impossible because of her being in London,

So Jared (Ginsberg) mentioned “well what about Kyle (Morland)” you know he is right here and I had never even thought about him as an option, or even if he would be interested, so he immediately said yes,

Now collaboration has not necessarily been a defining feature of your work, but you’ve never shied away from it, how do you find that process, working with artists, getting feedback?

It’s the first time I’ve worked with another artist on an equal basis to be honest with you, I’ve called it collaboration before but, I don’t know if it was fully collaboration because it was always my family members, and they are not artists, so the conceptual side would always come from me, certainly I would leave a space open for them to at least have some kind of input, but with Kyle it was a bit different, I didn’t want to overshadow. His forms and his structure are still very present, and I thought it was strong enough for me to inhabit,

Igshaan Adams

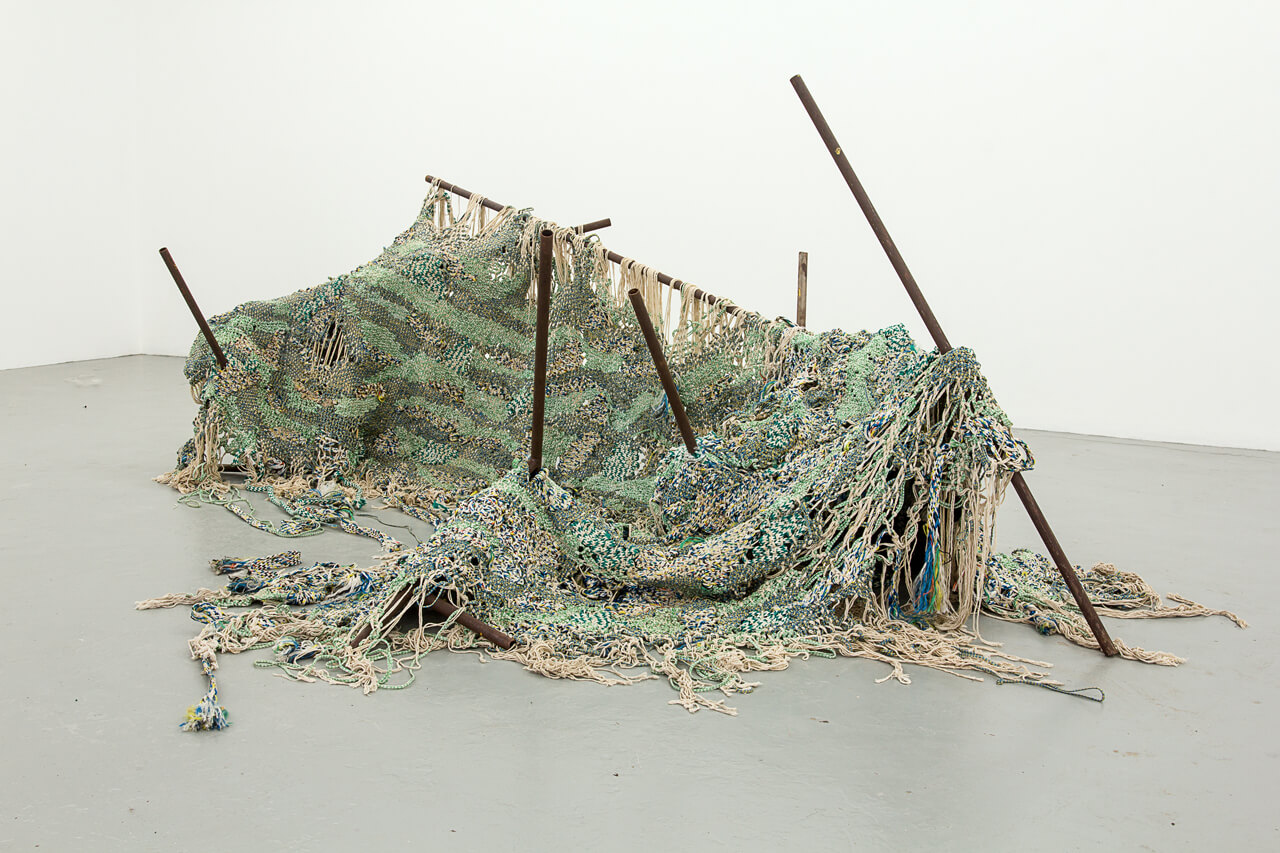

Stoflike Oorskot 2016

In collaboration with Kyle Morland Woven

nylon rope, string and mild steel

Image courtesy of the artist and blank projects

Just as we speak further about going 3D, I’m interested in the content of the tapestries…I know you used prayers translated into shapes on the surfaces,

I’ve kind of walked the journey (I hate to use that word) with Islam. I was born Muslim in a christian home and then left, didn’t want anything to do with the religion. I wanted to be gay, and I couldn’t do both. Then things just kept changing and at some point I felt a bit of a distance, so the starting point of the prayers was my yearning to go back to the origins of Islam. So in all the prayers, you’ll notice, I went back to the first prayers in the Qur’an, back to the first prayer I was ever taught, the first prayer I ever taught myself as an adult wanting to engage more with Islam and wanting to know more. So there was a desire underneath it that pushed me to all these prayers, they all meant something to me…

I think for any Muslim also, whatever’s happening in the world and I try for it not to, it does affect you. So one of the prayers I focused on was Al Kafirun or The Unbeliever, where very beautifully the Qur’an says oh you non-believer, you have your way, I have my way, your way will never be my way, and my way will never be your way, but to each is his own way, we both have our separate ways. I know there are people with a different interpretation of that, but you have to look at the context, when the prayer was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad and whatever was going on there. For me it’s very simply a beautiful confirmation that there’s room for my belief, versus other peoples’…

You’ve always said that your mats and weaves can be read from either side…

Exactly, that’s important for me too. The one side is illegible, or sometimes on both sides. What happens in the weaving process, to the actual letters, and often the way that I’ve used the actual material itself, with the intention of abstracting these, so even someone who reads arabic and understands, will battle to read it…

So this abstraction thing I feel also is my relationship to Islam, because I don’t speak arabic, I understand certain parts and certain phrases, and the prayers that I do now have a collection of carpets of, are the prayers that I’ve put effort into making sure I understand each of the lines when I say it, so that the meaning becomes felt…

I suppose the move towards abstraction, with the three dimensional looms and forms are a natural development…?

exactly, a continuation of…

So, earlier when we were speaking about how you physically occupy the space that Kyle is offering as an artistic conversation is quite a nice way of describing it, can you elaborate…

It’s funny, the way that I looked at it was that I was dressing his forms, because I find the simplicity very beautiful, that was the approach… because of the carpet that is so big and heavy, it can completely overtake the form and he gets lost and there’s no point in me choosing another artist to work with at all, so its finding that balance between dressing him up a bit, keeping the actual structure and the form and inserting my structured chaos…

Speaking of your structured chaos I’m quite fascinated by your materials and your method. I know you did quite a bit of mentoring at Philani, can you speak about how some of these skills developed in the early days up to the point where you were conceptualising your medium.

So I worked at Philani for five years, its a child health and nutrition centre in Khayalitsha, and two of the woman that worked there over the five years, they work for me now in the studio here. My position there was a facilitator teacher where I would help the mothers who were weaving already. They used t-shirt material to weave with and the imagery was also scenes from the Eastern Cape where most of them were from. So I would have to help them develop their imagery and they taught me to weave… so I sat on this idea for a long time, I wanted to weave and thought about it but I could never find the right material to weave, or at least material that excited me enough to want to weave with, I knew that I would never want to use the material that they used…

Did they just use t-shirt material…?

Well they use the textile company that produces the material, they cut it and all these thin strips that are left over from the cutting process to weave with. So when I started thinking about finding something, because eventually I had to do something. My starting point was to unwind the Islamic prayer mats that I used in the past, so I have bags of offcuts that I had kept since then. So I started unraveling them wanting to get my own thread with them, and you know that symbolically this was a nice way of doing things…undoing and redoing which would have made sense with the way how I see myself as a muslim. You know the idea that you almost create your own form of Islam that suits you, there are things you choose to honour and there are certain parts that are too big to take on at that point…

But then the company wouldn’t let me, and I tried doing it myslef and to weave those massive tapestries that way would have taken forever…

Why wouldn’t the company let you? What do you mean by that?

Because they have specific materials, the machines are made for those materials and they would have to reset everything and they weren’t willing to go through all the effort, they were quite a large company.

But they were making rope already and it was kind of what I would imagine the rope would end up looking like aesthetically, and that was the closest I was ever going to get anyway, and it was beautiful on its own. It was their own recycled materials that they throw back into the machine and what ever colours were left over, that’s what comes out of it. So each of these bails of rope were completely unique and will never be reproduced and that was exciting for me, there was this discovery about how things change on the inside of the bale, sometimes I’m able to see and sometimes I’m not able to.

And would that have a direct effect on whats coming out… so how much do you make choices and let your materials dictate?

Well, I have so many of these ropes and I’m able to choose and edit the rope itself so it creates the desired effect. Moving one thin line or a few lines within the grade that I might want, or using a couple of different ropes that you might not even notice in the carpet when it’s woven together…

Your surfaces have always been quite laden, starting where the prayers were quite legible and then the surfaces becoming full of tassels and unfinished textures. I thought it is quite interesting how the process as its developed tends to have this unfinished quality that goes on and on and on, that seems to resist the borders…

Well, it’s the process of abstraction that we spoke about, and that also helps with unravelling…I think it comes from previous works, my last title was Parda, and throughout my practice there has always been the idea of veils or unveiling. Getting closer, there’s that same sense that the not so clear, is still there for me, allowing me to be able to see other things.

and the title of your show?

Oorskot

…and so?

It’s an Afrikaans words, and I had a few conversations with my Afrikaans friends about what it actually means. So one person told me that it’s quite an old Afrikaans words and she remembers her grandmother using it quite a bit, and I think generally it’s used to describe mortal remains of a dead person. Well, this friend of mine Gerda (Scheepers) had this idea that it might have a certain religious connotation, with oorstok meaning the mortal remains of a person which is not that important anymore, because the soul has left and the body remains. The oorstok meaning what’s left over… but it also means surplus or excess which is another use of the word,

So the dead body is the excess of that which held our spirit?

Yes, surplus also made sense because it provided the starting point…I went back into my studio…I have this habit of collecting things from the studio, and just putting it away in bags and bags, so I went through my studio and looked at what I had there and that was the starting point from just left overs. So did Kyle (Morland) actually, as we started with this collaboration…he looked at the steel that was left over from various bodies of work and we started just putting things together.

Igshaan Adams

Ontgroei 2016

Found wire fence, wood, string, beaded necklaces and wire

Image courtesy of artist and blank projects

Because your forms now, the works that I’m seeing, have that very corporeal quality… they remind me of bodies in a way that are very lucid but are also very unidentifiable. Since your first show at the AVA you’ve always flirted between a mixture of installation, sculpture and then two dimensional work. How important is it for you to occupy those different arenas of medium and not be confined to one specific mode of working?

I was aware of it from the beginning, and it was important to me, yes. I think it might come from the painting, I started out as a painter, that’s how I was trained. I was taught the very traditional way of painting with very little conceptual practice involved. But I grew to realise that I never really loved it and I felt completely trapped within that medium for a long time. When I discovered and started using different materials and things from my home and I resonated with the different textures and things, it all just clicked in and I loved it. It felt so open and there was so much, and you can’t do it all at once, so it was always my intention to experience it all and not to fall into that same trap that I fell into with painting…

So the AVA was your first endeavour into installation?

…that was my graduation exhibition after Ruth Prowse, that was one version of it actually, in the original I went full out where I even painted the walls… The Ruth Prowse school of art was someone’s home that was turned into a school. I always felt because it was so small – there was mainly women working there, I think there was one male lecturer at the time – there was such a feeling of being at home and a motherly engagement with my lecturers so that was the route I took. I looked at my own domestic environment wanting to understand how am I a product, both physically in terms of domesticity and psychologically in terms of how the domestic represents my psychological environment.

How important was that process to discovering your work as it is today? Because you’ve managed to join the domestic with quite high end minimalism. How did that blend between the two come about?

With the weaving….? Well, I sat on it for a while, I tend to do that, to sit on ideas. So when I thought it through I was nervous about it because of its association with craft. And it really made sense when I discovered the material, that’s when I really got excited about the weaving.

There’s always been this art/craft debate… a lot of the time these incredibly versatile mediums get stuck in the vacuum that is created by these kind of debates. From someone whose managed to transcend that boundary, what do you think lies at the base of it?

Now I think it’s completely accepted, to the point where its almost trendy and fashionable, the craft aspect of things. Its just a relatable thing to me, it’s a thing I grew up with, my family was very crafty always, and it’s something I was naturally drawn to. I think after I got over this fear of how it will be received and just enjoyed it for what it was, it was okay.

I suppose that’s the other question, your work has seen an incredible amount of interest and as you alluded to just now there has been a revival of these kinds of techniques, what’s your critical response to it finding this mainstream adoption?

I think it makes sense, it might have something to do with technology. It’s almost a response to this hyper technological age that we’re living in and now there’s a desire to go back to how things were done before. It would be easy for me to get a company in China to make these tapestries but I love making things and I think other people might feel the same. You find that pleasure of making with your own hands..

How important is it for you to throw things away and self edit?

Very, I’m happy to fuck up and let something not work, I think that’s important. I’ve also thrown things away that now I regret, in hindsight actually I shouldn’t have. But also throwing something away is a good way of trying to start over again because while you’re making, you get so caught up in things that you really look at what’s working and what’s not and you can pull from it.

Tell me about the hanging works? Are these a new development or is it something that you’ve been working on for some time?

A couple of years ago I realised that I need to fight with myself in the starting process of making a body of work. I need to get through all the crappy idea’s before I get to the good ones, so I always had something, some kind of structure in the studio where I would go and just vent all my frustrations where there was no expectation that the result would be anything good. It was just about getting it out. Then once I’ve creatively exhausted myself, that’s when I can find something from a still point and that stillness hopefully gets translated into the object.

But in this case, this mess became the work because I threw everything that I had given up onto it and just let it be. In the past I would have just thrown it away.

[…]