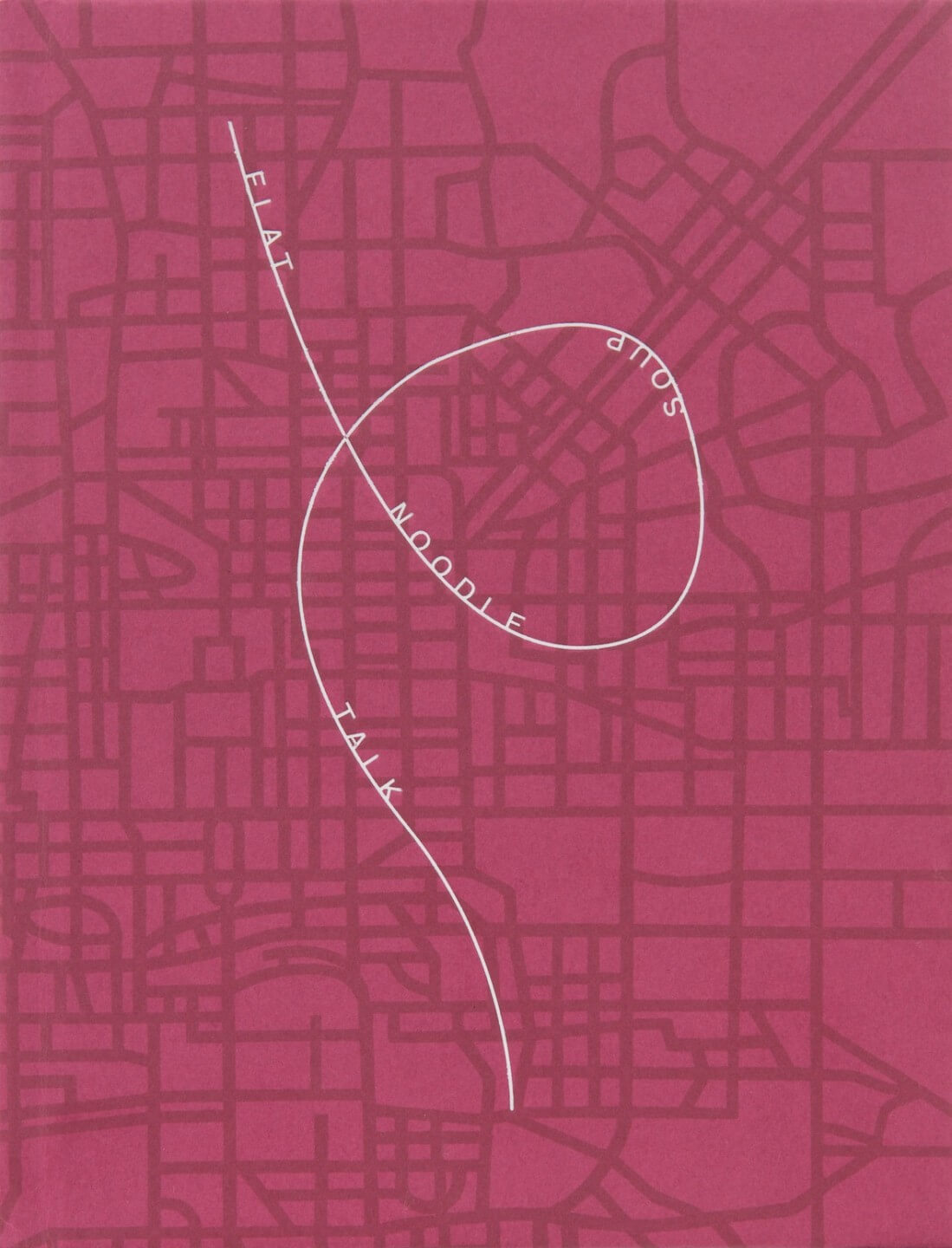

Pieter Hugo: Flat Noodle Soup Talk

In a 2015 interview photographer Pieter Hugo recalled, “a conversation with Guy Tillim – I don’t remember if it was a conversation or an argument – in which he said he doesn’t want to photograph anything he doesn’t want to look at. I thought, well I photograph corpses and I don’t really want to look at these things but I want to challenge myself, I want to challenge my own comfort zone in a way. And this is something I’ve wrestled with over and over, whether I agree with him or whether I think his answer is disingenuous. It’s something that has stuck with me and it’s a conversation I have with myself over and over, like why would I want to do that?” [1]

Zeng Mei Hui Zi, Beijing, 2015-16

It’s a conversation between the two photographers worth recalling as both have new books published by French publisher Éditions Bessard dealing with their experiences of Beijing. For Hugo who has made several trips to the Chinese capital, the work collected in Flat Noodle Soup Talk presents continuities with some of his earlier portrait work, most particularly perhaps with his 2007 project Messina/Mussina in its examination of the changing nature of Chinese society in the moment of its move from a collective, seemingly uniform identity towards one where individual expression has begun to visibly flourish in the wake of the country’s rise as a modern empire and economic juggernaut.

Flat Noodle Soup Talk

The book, a slim, small-format, unprepossessing volume with what appears to be an abstraction of a map of the city on its cover, guides its reader with only one piece of text – an epigraph which quotes from Freud’s Civilisation and its Discontents, in which we are asked to, “by a flight of imagination, suppose that Rome is not a human habitation but a physical entity with a similarly long and copious past – an entity that is to say, in which nothing that has once come into existence will have passed away and all the earlier phases of development continue to exist alongside the latest one.” Thus are we drawn into Hugo’s distinctive, contemplative and quietly human series of photos which combine still-life, group shots, portraits and a few nudes to thread a complex journey through the cracks that have been thrown up between China’s history and its rapid embrace of modernity.

Untitled, Beijing, 2015-16

The distinctive star of a Mercedes poking through a tarpaulin; the defiant gaze of a gay couple in their apartment; the hooded glare of a young man in hot-dog decorated boxer shorts, a cigarette in his hand, tattoos on his arm and perhaps in a moment of vanity, a pair of spectacles nestled at his feet; the slightly stiff newlyweds on their bed below their happy wedding portrait in which they hold a polaroid of themselves kissing – three moments and emotions held in one frame – these interior shots seem both beyond and very much of their time and place and about not just China as an emerging space of interest for outsiders but also one very much inhabited by people with their own ideas, passions, and ways of looking at the world.

Tan Yunfei, Beijing, 2015-16

With no information provided about the subjects – not their names, the date of the photos or the locations – there is a large amount of space provided for the viewer to construct imaginative narratives of what life beyond the lens might be like but small details of interior décor and dress provide elusive hints. Still-lifes of dressing tables and sideboards create their own story of personal import and national identity. Finally there are also the gently whimsical shots of fruit and vegetables on what appear to be floors, sometimes in pots of water, which give brief glimpses into the outside world and its eternally present natural forces.

Peng Wang and her family, Beijing, 2015-16

In one of the world’s biggest and ever-growing cities there are still moments of quiet isolation that Hugo finds and manages to convey thanks to his focus on the humanity of his subjects and their search for their own identity in amongst all the chaos and bustle of the heavily industrialised world in which they live.

Deersan, Beijing, 2015-16

While Hugo long ago brushed off critical accusations of exploitation and exoticisation in his own search for artistic challenges, it’s hard to throw any such criticisms on this small but intriguing body of work, which evokes empathy rather than highlighting oddity or cultural differences. In this case perhaps Hugo has shown us something he wants to look at with sensitivity and appreciation for the ways in which so many lives and ideals are far more universal than exceptional and echo the constant struggle between the forging of our identities as individuals in the face of the demands of social norms and pressures, which so intrigued Freud almost 8 decades ago.

[1] Hansi Momodu-Gordon, Nine Weeks, published by Stevenson 2015.

All images © Pieter Hugo. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yossi Milo, New York

Published by Editions Bessard | 2016. Hardcover, 88 pages | ISBN 979-10-91406-48-2 | Price: R1 000 | Edition of 500