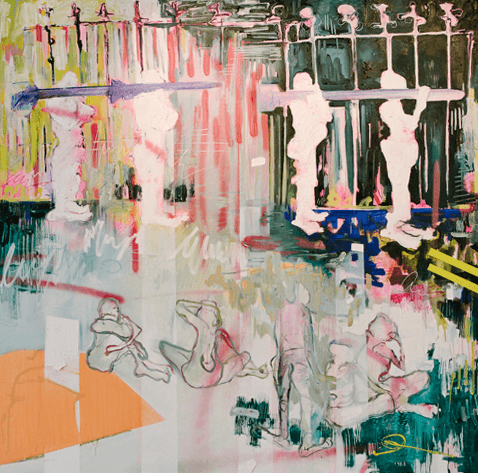

Non-people people: Elize Vossgatter’s ‘Limp’

Looking from the outside in

Oil paint, beeswax, spray paint and tape on cardboard

1470 x 1470mm

2016

I’m walking through the Smith gallery with curator Amy Ellenbogen. Structurally the space is perfect – two vaulted rectanguler rooms bisected by a central glassed atrium flooded with natural light. Running down the spine of both rooms are broken plaster tubes which echo sticks of chalk, or, as Ellenbogen sharply notes – unlit cigarettes stained with lipstick. Roped and cabled to the roof, the plaster tubes also suggest limbs – white limbs – strung up, limp, bereft of function.

It is whiteness which Vossgatter considers – a whiteness reduced, repackaged, strung together along a conveyor belt. As to where these limbs are destined is unknown – they simply hover, mute, as if frozen in place. The simplicity of this spinal installation is unsettling. Stained with soft pastel markings, it is apt that Ellenbogen recalls the pinched lips of a middle-aged woman, skin soured by too much sunlight, bedecked perhaps with an ill-coloured mane.

But these vivid thoughts which Smith’s curator incepts in my mind cannot shake the installations visceral-yet-abstract force. To limp, for Laurie Anderson, is to walk and fall, it supposes a disability and pain both physical and psychological. One senses the artist’s own disassembled whiteness, a whiteness brittle, broken, adrift. This after all is 2017 in South Africa, a country on the verge of annihilating its redemption vision of a post-racial world, a vision in ruins worldwide as I pen these words.

1990, the year which famously commemorated the unbanning of the ANC and the liberation of Mandela, was also, however, the year in which J M Coetzee published Age of Iron. The ‘iron’ in the novel’s title refers to the revolt of youth – a revolt which, given the violence afoot today, can also be considered prescient. For in Coetzee’s vision we have never transcended our brutal past. ‘You know this country’, he writes, ‘There is madness in the air here’. As for our ‘white cousins’? Coetzee, who quit this land for Adelaide, Australia, knew then what we cannot shake now: That there is no place in this aggrieved world for those he regarded then as ‘soul-stunted’ , those ‘white cousins’ who spin their lives ‘tighter and tighter’ in a ‘sleepy’ cocoon –

Swimming lessons, riding lessons, ballet lessons; cricket on the lawn; lives passed within walled gardens guarded by bulldogs; children of paradise, blond, innocent, shining with angelic light, soft as putti. Their residence the limbo of the unborn, their innocence the innocence of bee-grubs, plump and white, drenched in honey, absorbing sweetness through their soft skins. Slumbrous their souls, bliss-filled, abstracted.

As Amy Ellenbogen and I turn to the paintings, she remarks that the artist’s groupings – for no figure is solitary – are ‘androgenous non-people people’. Are these figures the fallout of this ‘abstracted’ world? Is this the weakness latent always at the heart of denialism? After all, who are these ‘non-people people’?

Musil’s men without qualities spring to mind, as do Eliot’s hollow men. Is it correct, however, to see these abstracted and voided figures as ‘white’, as representative of a privileged and exclusionary caste? I think that bio-politics – a politics that wages war against the rights and dignity of the body irrespective of colour or gender or caste – cannot so easily be cordoned off. Yet still, it is what we do: We separate people, herd them, fix and thereby diminish them. Is this what Vosgatter is telling us?

A week before the exhibition’s opening I am walking through Observatory. Laden with groceries, my body bent, the artist stops her car and offers me a lift home. The engine idles as we speak, then she snaps the key. In silence we resume. She is anxious. ‘Limp’, she says, and I immediately recognise the inspiration for the title of her exhibition. A hobbled whiteness is the artist’s theme, one she shares with Kate Gottgens whose most recent solo exhibition was called ‘Famine’. Both words express a lack – both are lacking. Against the delusory vision which J M Coetzee described in Age of Iron, a vision of South Africa’s ‘white cousins’ bliss-filled and ignorant, Vossgatter and Gottgens are now returning us to a darker threat of non-belonging, displacement, hunger, hopelessness, fragility.

The paintings with titles such as ‘White Balance: The tension between holding on and letting go’, ‘Silly white girls’, ’Calamity of power’, ‘Gilded burden’, ‘Blaming and shaming’, and ‘Sometimes you have to let go of the expectations that you’ve tied yourself up against’, reflect a mind, a heart, in ruins. Against expectation we find a nauseous doubt, against hope rancour. An uneasiness cuts through the paintings, and, sometimes, rage. For the world Vossgatter reveals to us not only announces the failure of democracy but the incipient return of civil war.

Silly white girls

Oil paint, beeswax and spray paint on canvas

1000 x 1000mm

2016

Compassion is dead as a dodo. It is not surprising, therefore, that in 2017 Pankaj Mishra should publish a book entitled Age of Anger. ‘We now see, all too clearly, a widening abyss of race, class and education’, says Mishra, ‘But as explanations proliferate, how it might be bridged is more unclear than ever’.

Well-worn pairs of rhetorical opposites, often corresponding to the bitter divisions in our societies, have once again been put to work: progressive v reactionary, open v closed, liberalism v fascism, rational v irrational. But as a polarised intellectual industry plays catch-up with fast moving events that it completely failed to anticipate, it is hard to avoid the suspicion that our search for rational political explanations for the current disorder is doomed.

It is against this impossibility that Vossgatter’s agonistic vision must be assessed. The crisis which she is experiencing, a crisis made manifest in her paintings, is not peculiarly our own. That said, it remains this country in which we live, and to which Vossgater is speaking. It is against the biliousness and indigestation experienced in the face of brute anger, against the bankruptcy of political correctness, the toxicity of leaden minds, against systemic cruelty and divisiveness, that the artist positions her nuanced unease. Her groupings of ‘non-people people’, while joined and seemingly in consort, remain psychically divorced, alienated, singularly shattered, for no balance awaits us. Rather, we teeter and crumble beneath an unbearable weight.

The techniques deployed to conjure this hopelessness are strikingly raw: a canvas pulled from its mainframe, a glutted density of paint, a fury of scratchings … corrugated cardboard, oils, spray-paint, glitter, bees wax, rope, wire, plaster. The words – WE ARE FUCKING ANGRY – dominate a painting bitterly titled ‘The triumph of nuance’. But there is no triumph in these paintings, other than the triumph of an artist who unwaveringly – as she quakes – thrusts before us our ‘current disorder’.

‘Limp’ is a masterstroke by an artist who knows that mastery has failed her. By ‘Looking from the outside in’ the artist, however, also reminds us that within this aggrieved and violent moment – a moment morally in tatters – we can and must confront our hopelessness.

As the African-American Nobel Laureate, Toni Morrison, similarly reminded us, in an essay published in in The Nation in 2015 and titled ‘No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear’ –

I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge – even wisdom. Like art’.

The spectators of descent

Oil paint, beeswax, spray paint and sharpies on canvas

1600mm x 1600mm

2017

*****