The Big Hole: Negative Space at WHATIFTHEWORLD

When writing Formal Analyses of artworks – back in undergrad, or in matric – special notice was always to be taken of the elusive realm of negative space. It gets you marks; acknowledging negative space lets you in on a secret that others think is only theirs.

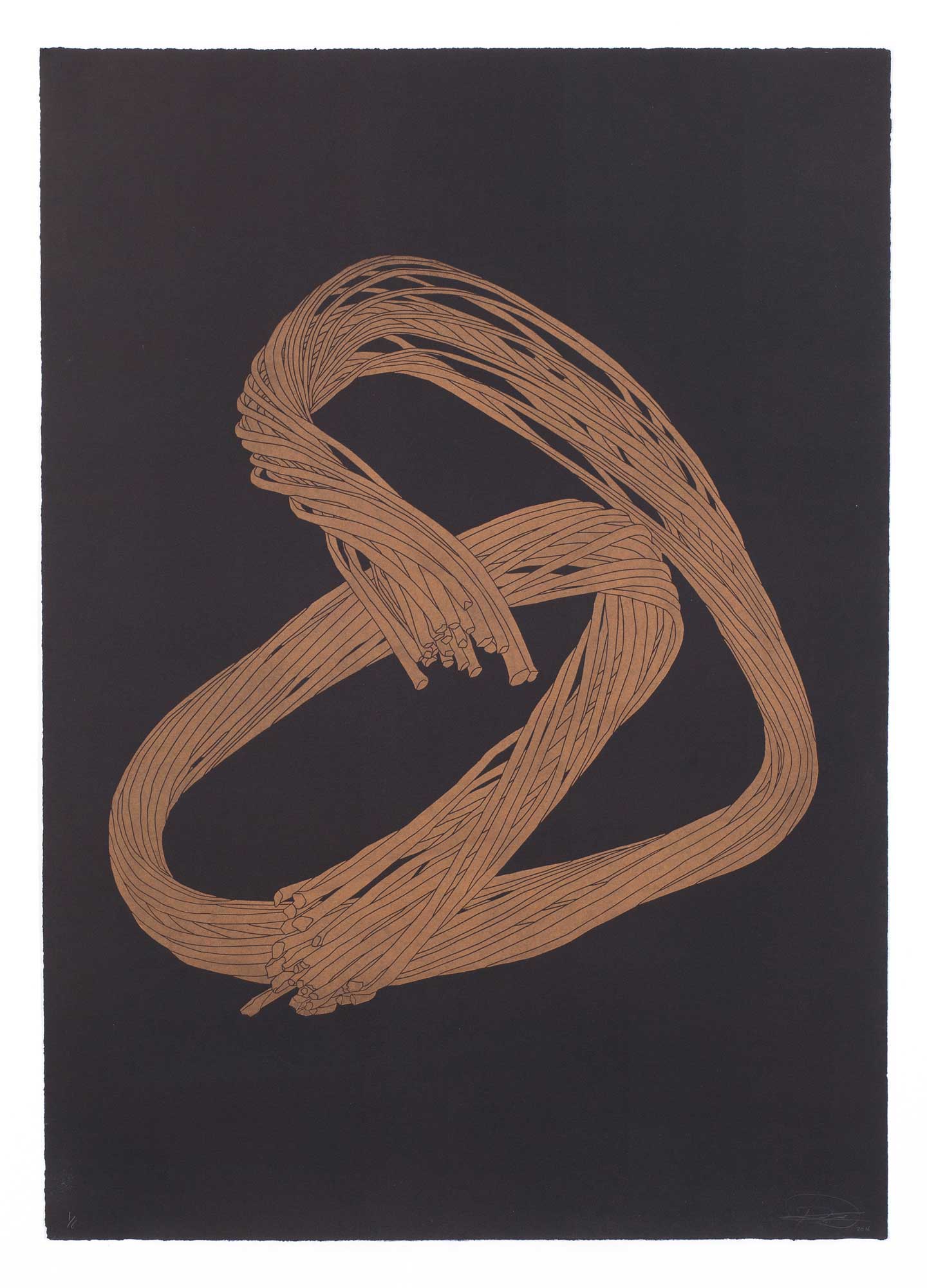

Scrap Metal Dealer Drawing 4 | Rowan Smith | 2016 | Linocut on Zerkall Litho 270gsm | 76 x 107 cm

It is a formal concept, claiming the background away from chaos into order. It’s what you don’t see, or what you’re not supposed to see, unless you are writing up a Formal Analysis (in which case you are very smug and clever to have pointed it out).

Endabeni 10 | Mohau Modisakeng 2016 | Ink-jet on Epson Hot Press Natural | 150 x 200 cm

WHATIFTHEWORLD’s most recent exhibition does its utmost to move these observations away from the apolitical – to not let the principles of balanced compositions pull focus. It uses the idea of negative space as a way to talk about power and social relations, with varying effect.

Appropriately, the running theme here is of land and landscape – the constant backdrop upon which power and oppression are visited and played out.

Lost Ground (Detail) | Michele Mathison | 2015 | Gypsum | 214 x 349.9 x 5 cm

(Negative Space is primal but receding.

It is eaten away by content,

and in a quiet battle with form.

It is eternal).

Wees Gegroet (Video Still) | Bronwyn Katz |2016 | Digital Video | 11:25 min

In Bronwyn Katz’s video piece, Wees Gegroet, her body turns and gesticulates inside a field of red dirt, taken from her home town of Kimberley. This is a town perhaps best known for its Big Hole – an open mining chasm ‘owned’ by De Beers, with historical stakeholders such as CJ Rhodes himself. The Big Hole is a wrenching, visceral metaphor and literal fact of negative space, formed from manual labour and racist, colonial exploitation. She doesn’t address the hole itself though. Not directly. Rather, she connects with the land it has disturbed – with the dirt that’s been subject to abuse and upheaval, but that persists as a part of the landscape, and as a player in cultural memory. She turns to face the cardinal points – North, East, South, West – greeting them, reclaiming them.

(Negative space is also those places ignored, cracks filled with weeds

What emerges despite all efforts to prune,

is the husk of a germinated seed).

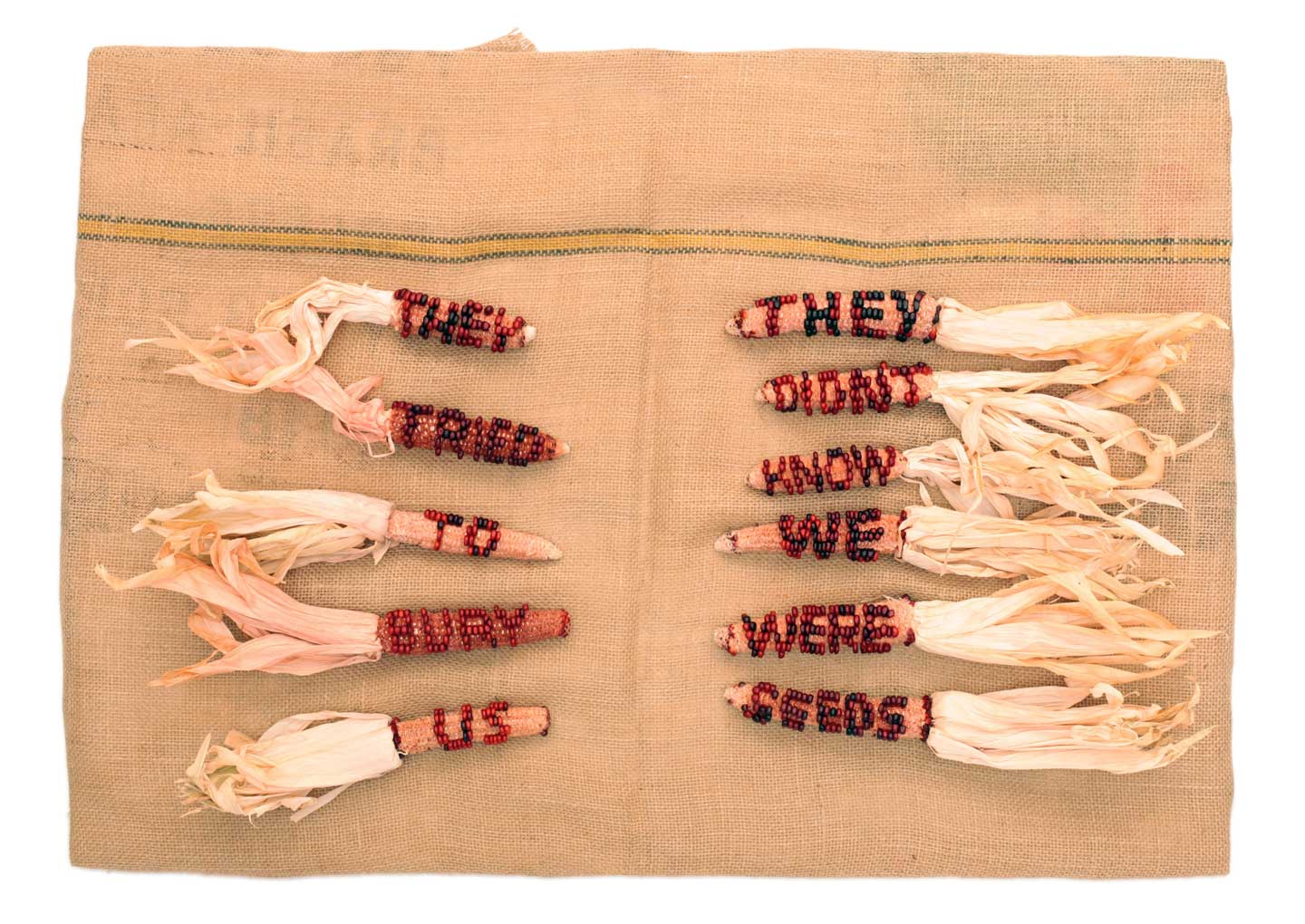

They Tried To Bury Us, They Didn’t Know We Were Seeds | Dan Halter (in collaboration with Oliver Barnett) | 2016 Heirloom mealies on hessian | 64 x 89 x 9 cm

I do wonder, though, what Dan Halter is up to here. White men artists have claimed so much of the foreground already. Must they now claim the background too?

With collaborator Oliver Barnett, Halter appropriates the revolutionary slogan “They Tried to Bury Us, They Didn’t know We Were Seeds”, used by the Zapatista movement in Mexico, and originally written by gay, Greek poet Dinos Christianopoulos. They weave this proverb into heirloom mealies in what I hope, but doubt, is a(n un)self-aware act of irony. What are they doing with this slogan? Do they mean to neutralise it, to turn it against itself? To turn it towards themselves? Who is being buried here?

Who is the “us” they refer to?

(Sometimes Negative Space pretends to be neutral but retains control.

When it is held by white men

It is a cipher).

Fissure (Detail) | Michele Mathison | 2016 | Steel and Stone Approx. 250 x 60 x 40 cm

Lungiswa Gqunta’s Lawn 1 stands as a counterpoint to the rich, pliable earth in Katz’s work, turning attention towards land which has been tamed and domesticated. It also cuts through the politics of Halter and Barnett’s ill-considered positionality, challenging the privilege of privately owned land, which, in a previously colonised country, is a privilege most often afforded to whites.

Lawn | Lungiswa Gqunta

2016 | Wood, broken bottles and petrol |

242 x 122 x 28 cm

The work is a wooden block stuck with broken coca cola bottles, sharp and filled with varying quantities of green petrol. It is a powerful conjuration of the beautifying, low-key ostentatiousness of the suburban lawn, and the physical and social control they exert on the environment. The threat is double edged – the shards of glass both turned to challenge the perversity of land ownership, and also indicative of the entitlement of white land owners, who will tolerate no ‘trespassers’ on their property. The spikes recall those cruel, jagged rocks installed under highways which prevent people from stopping to sleep or to rest.

No land can stand unoccupied. And occupation is at the discretion of those in power. Even if that occupation requires spaces to be forcibly empty; like acres of unused lawn, or the underside of highways, or park benches with polls which prevent people from stretching out. All space is contested.

Where negative space is allowed to exist, outside of the realm of concept or form, there is fear of what might grow. Or hide.

.

.

.

(Negative space is a phantom;

created the moment it is seen, disappearing the moment

you look away).