Michaelis in the age of FMF: Inside Operatives

2016 presented a long overdue dialogue at UCT’s Hiddingh campus. Almost half of the academic year saw its occupation by the intervention collective Umhlangano, a mixture of artists, actors and theatre-makers whose frustration with institutional culture pushed for an urgent necessity in re-politicising an art institution that has slotted itself so neatly into the kak rainbow-nation politik of post-1994 South Africa.

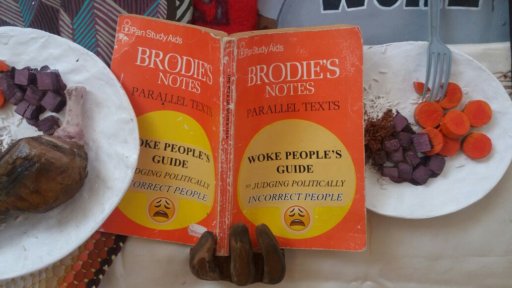

Dada Khanyisa. What is This Patriarchy You Speak of? (detail)

The Michaelis program has historically made it difficult to develop transdisciplinary* creative practices because of the obstacles placed in the way of students wanting to gain knowledge (beyond the foundational) in other university subjects. This is how the institution maintains its value – by producing ‘specialist’ artists, whose knowledge-base is within art itself, and essentially ‘unpolluted’ by the larger political situation. It is through the rewarding of anti-rigorous (anti-black?) art practice that the school maintains so much power in reproducing the somewhat flat commercial art scene we experience here… Touché, I guess.

Dada Khanyisa: What Is This Patriarchy You Speak Of? 2016. Wood, paint, fabric, rice and art.

It felt significant that some of this year’s graduates had encountered and continued to grapple with far more complex ‘curricular’ than had been developed by the formalised program. The participation in the disruption of the usual time-space paradigm of Hiddingh campus seems to be responsible for breeding a creative culture that opens itself up to dialogue, takes on the identity of cultural work and articulates to its audience more layers of self-reflexivity in exploring contemporary politics.

Asemahle Ntlonti: Amabali. 2016. Metal, glass and speakers.

Dada Khanyisa’s work is incredibly cohesive in this regard, blending the figurative and the conceptual in various painting works that form part of his show iNkosi iBenathi. Khanyisa’s graphic comic-style characters are occupied with numerous activities- from fun, to fun and irresponsible, to mundane- but their commonality is their absolute unconcernedness with our gaze, making their stories appear immersive, and carrying with them a certain complexity. The details of these images, for instance the book cover that reads, ‘Woke People’s Guide to Politically Incorrect People’ in the painting entitled What is This Patriarchy You Speak Of? leads us toward the artist’s own internal dialogue, one which is equal parts pressing and humorous, challenging conceptions around knowledge production in both formal and informal education spaces, and the hierarchies haunting this binary.

Xhanti Zwelendaba: Nozulu, Mpafane. 2016. Cow dung on balau.

This sensitivity to binary codes is mirrored in Xhanti Zwelendaba’s work QOBOBOQOBO, which, in a number of interventions, explores the way that colonialism’s know-it-alll attitude has created strange cultural binaries in its colonies that continue to split black subjectivity in painful and also somewhat arbitrary ways. In Asemahle Ntlonti’s sculptural work, we then consider how actions of resistance and disruption to these contradictions in the status quo are routinely met with force against black bodies. The quiet heaviness of her concrete and metal showers, and her police windows fitted with audio from student protests, reference Chris van Wyk’s apartheid poem In Detention which, through disturbing satire recounts common lackluster excuses for the murder and violent atrocity upon the bodies of black political activists by the apartheid police.

Altogether, there were a number of really interesting moments within this grad show – the poignant textual accompaniments to Lucy Robson’s Unmothered series, the ‘serious artists’ henriandnic, who are working in new and hilarious ways with relational and social interaction as art practice, the quiet prints of Mariam Moosa, the meta-meta-meta filmic art studies of Evan Wigdorovitz, and the skillful photographic interventions of Kyu Sang Lee, to name just a few – that I felt were really key in pushing collective practice forward.

The student protests are likely to start even earlier this year, so we should be expecting some more decent work from the next lot.

*the main difference between interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary practices is that the former works with a number of disciplines together in order to enhance the scope of the practice itself, while the latter’s objective is wider, using the necessary disciplinary practices in collaboration with one another as a mode of making sense of the ‘real’ world. For example, we might consider art therapy a transdisciplinary practice, where the collision of art making and psychotherapy work together not as an experimental collaborative project, but as a combination that produces a mode of seeing that works towards a productive and consequential understanding of one’s psyche.